The stories we tell ourselves

I’m reading a fantastic book by Owen Eastwood (Ngāi Tahu) called Belonging: The Ancient Code of Togetherness.

Owen is a performance coach who has worked with leaders worldwide.

His book centres on whakapapa, and how it is integral to our achievements.

Something that he wrote came back to me this week as the Government announced that they were scrapping the pandemic protection measures of isolation and Covid leave:

“Ideas like whakapapa people-proof tribal identity, ensuring that the transmission of culture down the line of people is not perverted by the agenda of individuals.

Many organisations create a vacuum around their Us story by asking external agencies to define it for them before they have deeply captured it for themselves. What comes back is often a story and message that it’s perceived the public want to hear, rather than the authentic story.”

- Owen Eastwood

What is Labour’s story?

According to their website, “The New Zealand Labour Party’s roots lie in activism for workers’ rights and democratic reform, which can be traced back to at least 1840. …The Labour Government remains committed to key issues such as health, education, child poverty, and the environment, while working towards a brighter future for all New Zealanders.”

Given the clear implications for the spread of Covid in the workplace and the collective shrug from MPs in response to that stark, unequivocal risk, I think it’s fair to question if Labour are no longer aligned to their roots.

I was at an event recently where a key quote that struck me was “for me, when policy making, it’s always about the evidence and the lived experience.”

I struggle to believe either of those things were brought to the policy making table for the pandemic response decisions.

Experts and lived experience advocates have been calling out the stark health impacts of Covid for years now.

The data is unequivocal.

People who contract Covid-19 are 80% more likely to suffer from epilepsy/seizures, 43% more likely to develop mental health disorders, 42% more likely to encounter movement disorders, including tremors and other Parkinson’s-like symptoms.

Clinical doctors and pathologists have noted the onset of Alzheimer's disease in a variety of Covid-19 patients - including young adults.

People with Covid-19 reinfections could be twice as likely to die and three times more likely to be hospitalized.

Three in five Long Covid patients have organ damage a year after infection.

Covid can cause damage to the heart on a cellular level that can lead to lasting problems, including irregular heartbeats and heart failure.

Covid impacts are categorically not “mild” or “like the flu”.

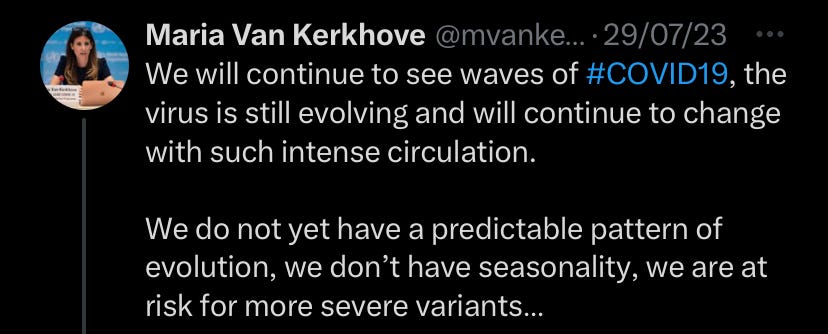

Covid continues to evolve, and WHO are very clear that Covid is still a concern, and that “Governments need to sustain critical actions to prevent infection.”

There are now no protections in place to stop the spread of Covid in New Zealand.

Meanwhile, nonsmokers who are exposed to secondhand smoke at work increase their risk of heart disease by 25%–30% and their risk of lung cancer by 20%–30%, and are susceptible to immediate damage to the cardiovascular system.

The Smokefree Environments & Regulated Products Act 1990 requires all internal areas of workplaces, licensed premises & certain public enclosed premises to be smokefree and vapefree. The purpose of these provisions is to prevent harmful exposure to secondhand smoke for non-smokers.

The Act was passed under a Labour government.

Why would we allow workers to be exposed to Covid when we can prevent it with isolation periods and other tools?

Why would we cause harm to the population’s health by refusing to take the clear impacts of Covid seriously?

The bottom line isn’t that Covid is over. We should be questioning why Labour has zero interest in acknowledging, (and paying for), very stark and ongoing health impacts.

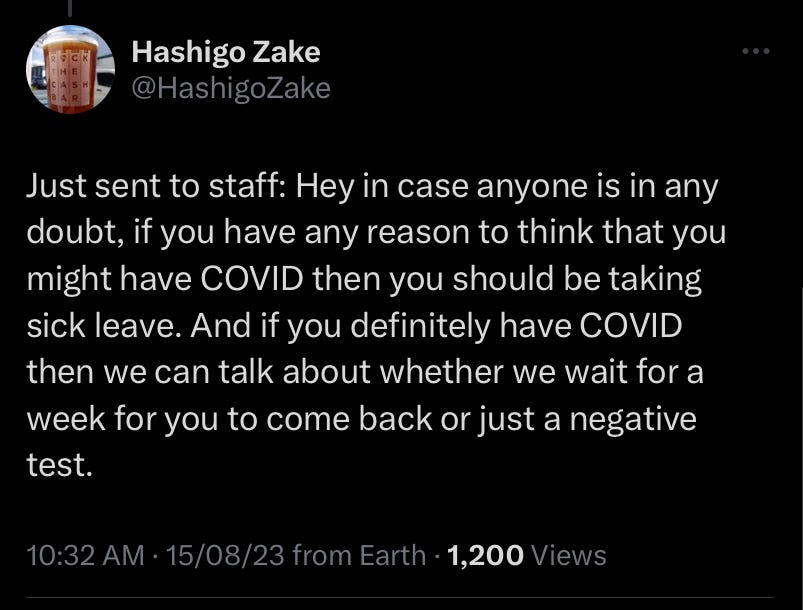

There are employers in New Zealand doing what we should expect our Government to do - setting clear expectations for providing a safe work environment.

Because we are not doing that at Government level, a few things are about to be tested with specific regard to Covid:

“Under the Human Rights Act 1993, an employer is legally obliged to take reasonable measures to meet an employee’s needs in relation to a disability. This is also described as making “reasonable accommodation”.

The New Zealand Disability Strategy defines disability as per article 1 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. It includes “… those who have long-term physical, mental, intellectual or sensory impairments which in interaction with various barriers may hinder their full and effective participation in society on an equal basis with others.” This is based on self-definition.

This means that, regardless of your workplace’s policies, employees have a legal right to “reasonable accommodations” in the workplace.”

“One in 10 people who’ve had Covid-19 are affected, and some estimates place the ratio is as high as 1 in 5. The risk increases with reinfection. It’s already an issue in the workplace, for employers and employees.

Early signs are that Long Covid will have worldwide workforce implications. In the UK, 25% of employers cite Long Covid as a main cause of long-term sickness absences. According to one New Zealand study, there are potentially between 300,000 and 400,000 long haulers in Aotearoa.

The exact prevalence of this post-viral illness is still unknown. But experts and advocates say the sheer weight of data about Long Covid’s impacts means the need for relevant policy is urgent and undeniable.”

The Health and Safety at Work Act 2015 “requires that all workers and others are given the highest level of protection from workplace health and safety risks, so far as is reasonably practicable. This includes risks to both physical and mental health.”

I raised these considerations in regards to Covid with some health and safety representatives not too long ago.

The response?

“What is the government doing about it?”

The entire reason we legislate policy is so there’s consistency in how people are treated, and so that the risks they are exposed to are minimised by law instead of vibes on the day.

If you want people to be exposed to serious health risks while working for you, and your key concern is “people should be exposed because I don’t want to pay sick leave” congratulations, your values are both terrible and consistent with the approach to 18th century coal mining.

There should have been people at the decision making table who created space to hear from lived experience advocates and from experts who understand the long-term health impacts of Covid - and who spoke up to ask where they were.

It would be great if we could treat Covid impacts with the same gravitas we once applied to the impacts of smoking - given that Labour’s story is about “remaining committed to key issues such as health… while working towards a brighter future for all New Zealanders.”

Is that an authentic story - or one that it’s perceived the public want to hear?

That so often seems to happen in politics - doing the minimum, skirting the edges of what might be possible while still staying comfortable.

We can do better.

We can create policy, knowing it’s the right thing to do, without second guessing or inching slowly towards it or denying that it can be done, that the time isn’t right, that there’s no budget or resource or authority - or clear cause for concern and for action.

We’re the people who can make those calls - we just need to have the courage to act on the need that is so clearly in front of us - and remain true to our story.

“Hope locates itself in the premises that we don’t know what will happen and that in the spaciousness of uncertainty is room to act.”

- Rebecca Solnit